Dedication

Introduction

Dan Ariely

Walter Bender

Steve Benton

Bruce Blumberg

V. Michael Bove, Jr.

Cynthia Breazeal

Ike Chuang

Chris Csikszentmihályi

Glorianna Davenport

Judith Donath

Neil Gershenfeld

Hiroshi Ishii

Joe Jacobson

Andy Lippman

Tod Machover

John Maeda

Scott Manalis

Marvin Minsky

William J. Mitchell

Seymour Papert

Joe Paradiso

Sandy Pentland

Rosalind Picard

Mitchel Resnick

Deb Roy

Chris Schmandt

Ted Selker

Barry Vercoe

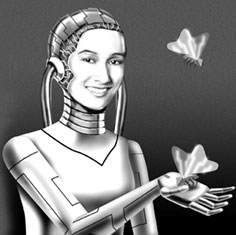

Cynthia Breazeal

Our robots are becoming more alive, and even more human. The boundary between biology and machines continues to blur as robots begin to metabolize organic material for energy, living tissue is grown over their structure, muscles are incorporated into their mechanics, and living brains are used to control their movements. In time, biological machinery will be harnessed to create robots that can grow and heal themselves.

Our robots are becoming more alive, and even more human. The boundary between biology and machines continues to blur as robots begin to metabolize organic material for energy, living tissue is grown over their structure, muscles are incorporated into their mechanics, and living brains are used to control their movements. In time, biological machinery will be harnessed to create robots that can grow and heal themselves.

Beyond the strict biological sense, however, our robots are becoming more like creatures rather than tools. This is more significant than the past trend to build "machines that X" (e.g., play chess, navigate routes, recognize faces, learn to juggle, or communicate in English). Now, robots are being integrated into our world, where they must interact with us in terms that we understand. Just as their biological counterparts, they must address issues of survival and self-maintenance in a complex, unpredictable, partially knowable, and ever-changing world.

Equally as important, we want to treat, interact with, and understand robots as if they are living creatures. Humans are a deeply and profoundly social species; study after study continues to reveal the impressive (sometimes bordering on irrational) lengths we will go to treat the simplest of robot toys as if they are alive, and to understand them as thinking, feeling entities. I do not think that this is wrong. It simply speaks to human nature. The deeper question is how does this fact impact the design of this emerging class of anima machina?

I am a creature builder. I want them to share our world with us, to communicate and interact with us, understand and even relate to us, in a personal way. As such, my fanciful robotic offspring are designed to be decidedly not human, and yet to possess human qualities. My research focuses on human-robot relations, the nature of social intelligence, and socially situated learning. I see all three as being the core interlocking pieces of a single puzzle.

Developmental psychology provides a wealth of insights and inspiration for my work, balancing evolutionary endowments with real-world experience and progressive learning. As adults, we possess an elaborate and pragmatic folk psychology—a social common sense that allows us to predict, understand, relate to, and interact with others. As we grow up we develop this folk psychology by engaging those around us. All the while, our understanding of our selves, of others, and of the relationships we share begins to emerge. I believe that the anima machina of the future will have to undergo a similar process, raised by people in human culture, to develop a social intelligence that merits being a part of society—to be accepted and valued, and to accept and value us in return. Future generations of such machines will be able to bootstrap this process from previous generations, but experience in the real world with real people will be necessary to adapt each to its immediate community.

Science fiction has depicted a future with such machines as sometimes something to fear, and other times as something to cherish. I have adopted a philosophy and approach that I believe is important in order to avoid the former and to achieve the later. But why try to build them at all?

This emerging discipline of creature building is equal parts science, invention, and art, with a dash of philosophy. This is fundamentally a process of creation and synthesis, rather than following the strict reductionism of traditional science. As with these disciplines, I build them to evoke our most human qualities, and by doing so help us to get in touch with the human experience. I build them to question our ideas of what it means to be human, and by doing so to force us to think beyond our flesh and biological makeup to those qualities that we cherish in our species. I build them to challenge our notion of machines, of what they are capable of, and of how special they can be. I build them to reflect upon how our brains and bodies work and to understand how they work—while at the same time humbling us and reminding us of how remarkable these gifts are. I build them to illuminate how we interact with each other, relate to one another, and learn from each other. I build them to reinforce how important we are for each other, how we shape each other's lives, and shape the people we become.

I find this to be of profound importance at a time in our history when we can start to tinker seriously with the fabric of our being, whether it is through manipulating our biological material or merging our bodies with technological devices. It is important in a time when our maturing mechanistic understanding of how our minds and bodies function tempts us to treat each other as "just machines." It is important when our machines are becoming more and more like us. As the boundary between our selves and our machines blurs toward unperceivable, our notions of what makes us special, what makes us human, and what makes us members of the human community may very well need to extend beyond simply being born that way.

Favorite recent read: The Diamond Age, by Neal Stephenson